Ok Deno, who are you?

Last week I posted about Node.js runtime, just to talk about this new JS runtime: Deno, an anagram of Node, which was developed by same engineer who made Node.js, Ryan Dahl. Why would you make a same thing twice? Ryan says that he wanted to fix things that he regrets nowadays. In this post, I tried to summarize changes that deno took, and compare with Node.js runtime.

First of all, pronounciation

Last year, Ryan used to cal deno dɛnō, but during TSCONF 2019, he mentions that most of users wants to call it as dinō, like dinasaur. I think both pronounciation fits well, as it is quite straight-forwardly written word.

Why Rust and Tokio

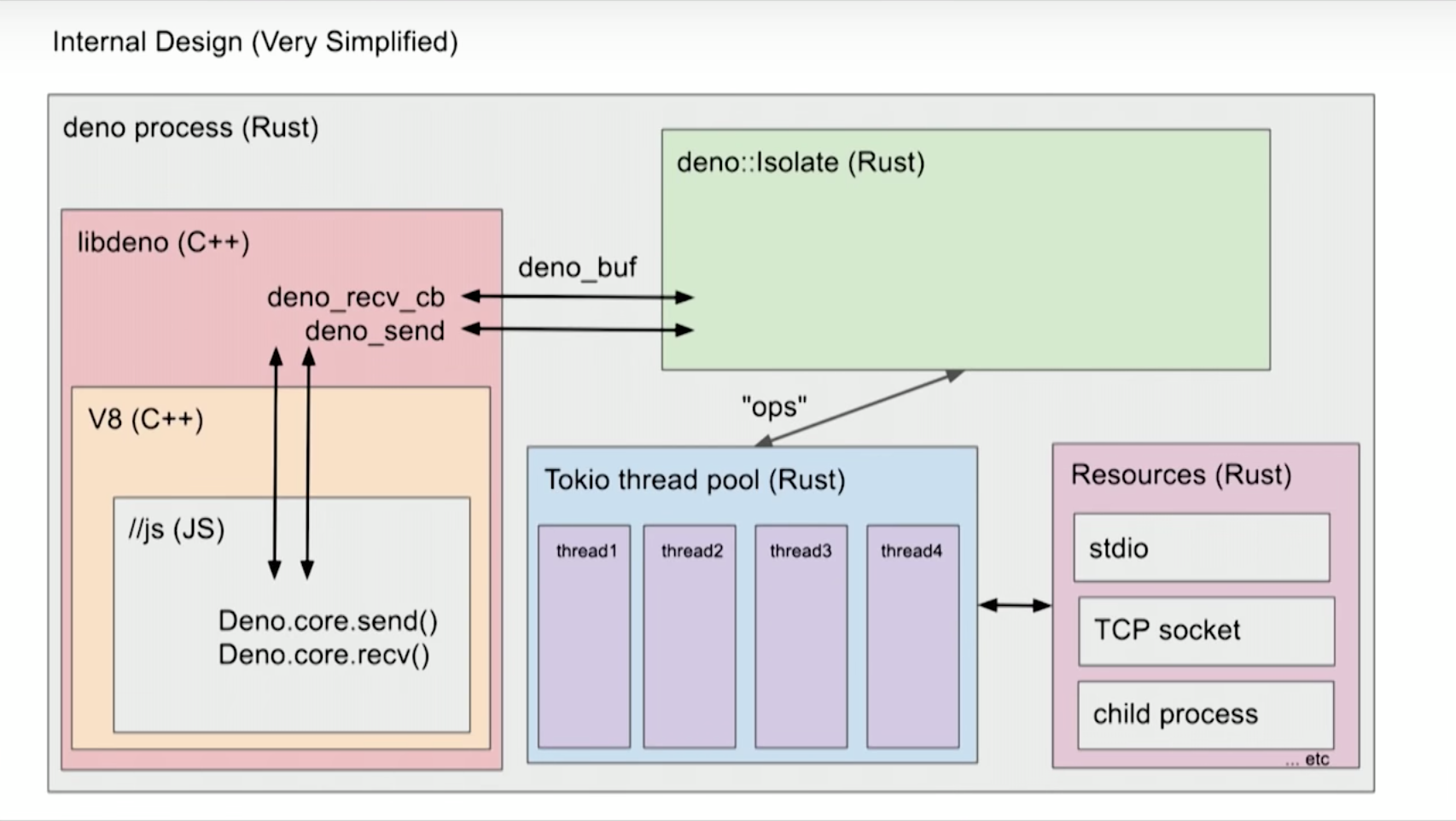

If you remember what I’ve talked about Node.js, JS runtime needs 2 essentials, which is javascript engine and thread pool library. Ryan have used libuv and V8 Runtime to build a Node.js, but this time he has chosen different tools.

V8 Stays. Which seems quite obvious (because more and more browsers are using V8 for JS runtime), but instead of libuv (which is written in C++) he used Rust and Tokio for new event pool library.

According to his speech in TSConf, this doesn’t imply deno is faster. He even says that you can still use node.js with no problem. But him being a rumtime compiler expert, writing runtime in low-level language such as golang or rust was inevitable to improve performance.

To him, the one and the most biggest flaw is node modules. Dependency hell and centralized npm is not an desirable state for a web structure. Even security issues (having no authority control over resources causing unintentional leaks) were regrets that he wanted to overcome.

Main philosophy: Deno does what OS does

You may have seen similar diagram in node.js runtime. But there’s one thing that deno has but node.js hasn’t: deno::isolate. Basically, deno do not trust user’s code, and let workers to run the process to read and run the code. Why? Because OS already made an great answer to the leveled authorization.

If you run JS code below on deno, you’ll face an error that you’ve never seen before.

const file = await Deno.open("/foo/bar.txt");

// Do work with file

Deno.close(file.rid);

Deno requests read access to "/foo/bar.txt". Grant?

[a/y/n/d (a = allow always, y = allow once, n = deny once, d = deny always)]

You need to grant an authorization, so the Web Worker(deno’s process) can access to the file with no problem. It is a similar error from linux, when you want to access a file with different user or group.

In order to make this code work, you should grant the authorization:

const file = await Deno.open("/foo/bar.txt", { read: true, write: true });

// Do work with file

Deno.close(file.rid);

these examples are from deno.land

file.rid refers the process’ resource id that deno has created to batch the job. If we look back the diagram above, libdeno becomes a wrapper to V8 which communicate with deno::Isolate, and deno::Isolate makes a ops(which is REALLY similar how syscall works) to thread pool to handle jobs. This design philosophy from OS allows deno to be more secure and frugal, to handle processes.

One and only package: deno

If we dig the history of create-react-app, we can easily understand how this application became so heavy, that installs thousands of modules just to resolve few dependencies and for the sake of just in case. Each create-react-app command costs that much of traffic to npm.

Then how deno solved this dilemma? Deno is the one and only package and the package manager, which brings third party module directly from URL:

import { assertEquals } from "https://deno.land/std/testing/asserts.ts";

assertEquals("hello", "hello");

assertEquals("world", "world");

console.log("Asserted! ✓");

Results:

$ deno run test.ts

Compile file:///mnt/f9/Projects/github.com/denoland/deno/docs/test.ts

Download https://deno.land/std/testing/asserts.ts

Download https://deno.land/std/fmt/colors.ts

Download https://deno.land/std/testing/diff.ts

Asserted! ✓

Instead of npm install We imported assertEquals directly from from https://deno.land/, and runs the rest of the code. If you run the code twice, deno uses the cached data from itself.

According to manual, there are various methods to deal with dynamic URLs adding a lock(–lock), or caching directly to designated directory, in case URL goes down.

What this mean, is that deno do not needs centralized package manager, and let users to handle the browser dependency directly. Having a thousands of lines in package.json without any context of usage, is not a single problem to deno.

Typescript

Last but not least, Deno is native Typescript runtime. I might talk about whole typescript in another post, but typescript is essential to deno, as it provides Typed array and fast prototyping.

libdeno and Ops (syscall thing I said above) communicates in Typed Array. It can be embedded as different tier application, and communicate with V8 engine with typed array. (Which in node.js was difficult, as it was extremely difficult to manipulate V8, and also insecure) Simply said, deno becomes a great wrapper made in Rust, which allows user to communicate with Typed Array.

Conclustion: I’m still diggin’ it

I watched few speeches from Ryan himself and other videos explaining about deno, and I thought this project means more to non-JS developers. Recently JS has been expanding to all around the tech field, and these rumtimes makes browsers and web environment much fertile than ever.

The point is: What web browser cannot do? Ryan said he was very interested in future WebGL, and I truly believe that newer JS rumtime will allow another developers (game, software, name anything…) to do their thing on web browser easily. Then, what should we, the typical front end engineer, need to do? That is a good motivation to grab a shovel and dig this massive deno’s footprints faster than anyone else does.